Samuel Beckett’s play Not I finds the stage immersed in complete darkness apart from a single spot of light covering an actresses’ mouth, which utters a four part monologue. Then the play ends. I am a huge fan of Beckett’s novels (I also love Waiting for Godot – I just haven’t read or seen any of his other plays), but even reading about Not I makes me wonder: would I enjoy this play? I might admire Beckett’s continual honing of his singular, existential idea down to something as small as a light on a woman’s mouth, but am I literally going to enjoy sitting in a theatre, watching a play comprising of just that?

Appreciating the concept behind a work can be quite separate to enjoying the work itself. And vice versa; I can enjoy black metal like Burzum but not enjoy, say, burning churches or murdering people.

The American band The Residents may have fallen on both sides of the Beckett/Burzum dichotomy over the course of their career (albeit to a far less extreme extent in either direction*) yet they always retain a uniqueness that has me coming back to them album after album.

*I’d just like to make clear that The Residents have NOT murdered anyone or burnt any churches.

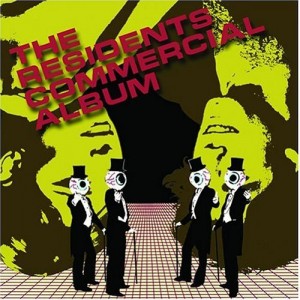

Concept and image almost appear more important than the music itself – you cannot mention The Residents without instantly picturing their infamous costumes. Dressed in tuxedos with giant eyeballs on their heads, holding canes and top hats:

They’ve maintained a level of anonymity throughout their career due to their outfits, never speaking in interviews and relying entirely on their management The Cryptic Corporation to act as their mouthpiece. The eyeballs have always been their main form of garb, with The Singing Resident changing to wearing a large black skull when his eyeball was reportedly stolen backstage one night. The Residents as a band have never spoken out to the public, although dedicated fans certainly have some good guesses as to who the people behind the masks are – particularly with the current costume of The Singing Resident (going by “Randy Rose”) which shows half of his face.

They also have some overarching and ambitious ideas. Concept albums might be enough for some bands, but The Residents take it to an extreme. I’ll elaborate further below, but there are a trilogy of albums where they released volumes 1, 2 and 4 (this makes no sense, I know). They made adventure games for the PC in the 90s, which mainly act like in-depth character studies. There are albums that were never meant to be released, then released. As I suggested above, not all of these are successful, but I nevertheless always admire and respect their dedication to the concept of a work.

They wear weird clothes, don’t talk and like big concepts – but what do The Residents actually sound like? It’s an odd mix of anti-musicality and sonic innovation. The music is generally quite simplistic, yet atonal, and eschews the conventions of popular music at the same time. Particularly in their early work, this gives off the feeling of childish whimsy – that there is a humourous, playful aspect guiding their writing. This isn’t to say they are afraid to go into darker territory – in fact, that’s where the bulk of their later material heads. Given all of this, it’s hard to classify the music of The Residents in a singular fashion. For every dissonant track, there’s one of melodious beauty. For every cheery tune, there’s one horrifying. This willingness to adapt also applies to their instruments, and the band always tried to incorporate the latest musical technology into their works (and although laudable, it unfortunately lead to the overabundance of MIDI keyboards in their 90s albums).

However, the most iconic aspect of their music has to be in The Residents’ frontman, the aforementioned Singing Resident. In his instantly identifiable southern drawl, he acts as singer, storyteller or manic noisemaker whenever the band requires it. I personally love the vocals, but they can be a point of contention amongst first-time listeners.

There’s simply too much material here to delve into entirely, so I’ll focus on a key selection. Since the band’s inception in 1966, there have been 145 releases. That is, quite simply, utterly ridiculous and some straight-up Frank Zappa-esque behaviour. Incidentally, The Residents were big fans of Zappa’s work, even covering “King Kong” and sending him a copy of it. Which, finally, brings us to their music.

Not Available – 1978 (or is it 1974?)

Duck Stab!/Buster & Glen might have been my first Residents album, but Not Available is the one that got me hooked. The history behind it piqued my interest instantly: The Residents commit themselves to the “Theory of Obscurity”, a philosophy purported by Bavarian composer N. Senada. The story goes that they recorded Not Available back in 1974 after their first album Meet the Residents, and lock it away in a bank vault only to be released when the band members could no longer recall the album’s existence. Not Available is then released to the public in 1978. Now, this all sounds quite ridiculous and given the name N. Senada sounds a little too much like en se nada – “in himself nothing” – the reality of this tale becomes questionable. But the band has stuck to their guns the whole time, and it’s an interesting bit of fiction regardless.

Not Available itself is the most operatic work of The Residents that I’ve heard, with multiple characters appearing over the course of the work each with their own voice – Edweena, a Porcupine known as Knowledge, The Catbird, Uncle Remus (nice Zappa reference) , The Enigmatic Foe and a chorus sung by The Singing Resident. But don’t ask me what actually is going on – although the album certainly is telling a story, it is cryptic at its most understandable, impenetrable in other areas. There’s … a love triangle? Maybe? That’s really all I can figure out.

So where’s the appeal? It’s in the execution. The eerie sounding chorus, the beautiful piano (particularly during the recurring motif in “Edweena”), the soulful saxophone and even the completely crazy back-and-forth between the manic sounding vocals The Catbird and the snivelling Enigmatic Foe in “Ship’s A’Going Down”. It all works together, becoming greater than the sum of its parts. We’re treated to opera, jazz and something that vaguely resembles rock. This inability to be pinned down to any genre, the (at first listen) completely baffling vocals, the weird history behind the album itself; I was destined to fall in love with Not Available. I would say if you’re already inclined to listen to off-kilter music, start here. If this is a little too intense though, there are some more accessible places to start…

In this vein:

Not Available is somewhat onto itself, so there isn’t too much to recommend that the band have done similar. However, the 2011 remastered release added seven minutes of instrumental music recorded but previously not on the album. Listening to both versions side by side, I’m a lot happier with the inclusion of this material. The extended synth-tastic passages in “Ship’s A’Going Down” and “Never Known Questions” are particularly inspired, adding majesty as well as relief from the more dissonant sections on the rest of the album.

The Commercial Album – 1980

The Residents themselves sum up the concept behind The Commercial Album in the album’s liner notes:

“Point one: Pop music is mostly a repetition of two types of musical and lyrical phrases, the verse and the chorus.

Point two: These elements usually repeat three times in a three minute song, the type usually found on top-40 radio.

Point three: Cut out the fat and a pop song is only one minute long. Then record albums can hold their own top-40, twenty minutes per side.

Point four: One minute is also the length of most commercials, and therefore their corresponding jingles.

Point five: Jingles are the music of America.

Conclusion: This compact disc is terrific in shuffle play. To convert the jingles to pop music, program each song to repeat three times.”

That’s right – 40 one minute songs, covering anything from saccharine pop ditties to sixty seconds of sonic insanity. What’s possibly crazier than the idea itself, is that most of the time it works! “The Nameless Souls” and “Ups and Downs” showcase some groovy bass playing – not something normally associated with The Residents work. “Love Leaks Out” also features some beautiful synth work – definitely one of the tracks I wished was longer. In fact, the run of tracks 14 through to 21 are utterly stellar, showcasing the crazy, the catchy, the stupid, the pretty and the sad. We also get some more experimental material with the rhythm-focused “Moisture”, the sheer noise of “Margaret Freeman” and some interesting guitar and violin work by continual Residents collaborator Snakefinger. As you’d expect, with 40 unique tracks attempting to be made here, not all of them work. Some tracks seem to cut off halfway through (“Secrets” in particular), others sound like rehashing of a track that happened 5 minutes ago. But in that is why The Commercial Album works so well. Don’t like something? Wait one minute and it’s gone! I can think of songs I love that have sixty seconds I couldn’t care less about, so this is hardly an issue for me. And given the good tracks hardly overstay their welcome, it’s an album that’s very easily to return to over and over again. In fact, I would say The Commercial Album is the most accessible way to get into the band.

In this vein:

– Duck Stab!/Buster & Glen is the other great, pop song orientated album. Primus’ cover of “Hello Skinny/Constantinople” actually introduced me to the band in the first place, and “Hello Skinny” is still one of my favourite Residents tunes.

– Chris Cutler and Fred Frith of Henry Cow contribute to sections of this album – although don’t ask me where!

– The Commercial DVD, released in 2004, 56 videos inspired by the album created by numerous artists and directors. It also includes the original videos, which you can watch below:

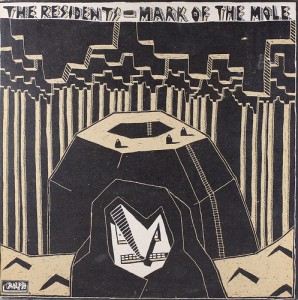

Mark of the Mole – 1981

The Residents go industrial. This is the beginning of what is known as The Mole Trilogy. Mark of the Mole is part one, The Tune of Two Cities (1982) is part two, and The Big Bubble (1985) is…part four. Just go with it, OK?

The story of Mark of the Mole looks at a race of people who live underground (the titular “Moles”), whose home is threatened by a storm. The Moles immigrate across the sea, meeting The Chubs – a race of chubby, aristocratic types. They welcome the Moles wholeheartedly into their society, but end up using them as cheap labour. As to be expected, tensions arise and reach all-out war in the album’s closer “Final Confrontation”. The story itself is quite ambitious , becoming even moreso over future albums – The Tune of Two Cities attempts to portray the music of The Chubs (easy listening jazz) and The Moles (industrial), whilst The Big Bubble goes even further and is sung entirely in the made up Mohelmot language (flashes of Magma, anyone?).

Yet I’ve always found Mark of the Mole to be far superior to its successors, and it’s entirely to do with the quality of the music. Each track is a series of movements, but really the album is meant to be listened to as a whole. The sound is harsh, artificial music made from synthesizers and is like nothing else I’ve heard before. There are clangs, clashes, beeps, boops and many other onomatopoeic words, but there are also unique melodies, usually in the form of a Mole-person chant. Perhaps it sounds strange, but I find there’s a warmth hidden in this album as well – I don’t feel repelled by the electronic coldness. I find myself wanting to go in, to go underground with these people and live alongside them.

Having said all of that, this was a bleak period for the band. The Residents’ first international tour was for this album and The Tune of Two Cities and involved a huge stage production, featuring stagehands acting out The Moles and The Chubs, scenery changes and Penn Jilette (of Penn and Teller fame) narrating the plot at points of the show. Although critically well-received, financially the tour was a disaster. This seems to be at least one of the reasons the subsequent albums weren’t as musically challenging, ambitious or unfortunately, as interesting. Until 1988…

In this vein:

I may not fully enjoy Mark of the Mole’s follow-up The Tune of Two Cities beyond its conceptual pull (each track alternates between a song from Chubs and Mole culture), but having said that I’m still quite partial to a few tracks – this guy in particular:

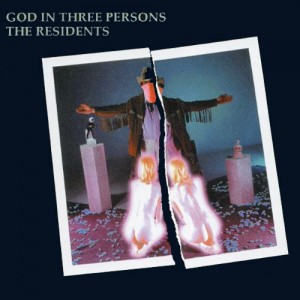

God in Three Persons – 1988

Every so often, I get asked by people to give them some music to listen to (#humblebrag). I try and tailor my selections to things that I think the particular person would actually appreciate, but I’ll always slip in some other works I just believe need to be listened to. God in Three Persons is one of those albums.

Having said that, I don’t believe I’ve been particularly successful with converting people to this album. This is a piece in particular you have to sit down, put on your headphones and concentrate on listening to. It’s an event, like going to the movies in ye olde times.

The cinematic quality of God in Three Persons seems to be understood by the band as well, with guest vocalist Laurie Amat acting like Greek Chorus in a play, providing foreboding (‘something’s coming, but not real soon’) and even literally singing the credits of the album in the opener “Main Titles (God in Three Persons)”. Of course, this is The Residents, so we are mainly dealing with The Singing Resident for vocals. However, in this instance his title isn’t exactly correct – the entire album is performed in spoken-word poetry with one continuous meter (think Poe’s The Raven).

This is an ambitious piece, yet feels intensely personal. I’m not even sure I can do the plot of this story any justice, but it’s the tale of Mr. X (our narrator), who meets a pair of conjoined twins with the power to heal people. He soon acts as their manager, exploiting their healing powers almost like a travelling salesman before the story takes a dark, dark turn when Mr. X begins to lust after the female twin. Exploitation, religion and sexuality are all delved into here, amalgamating together to reach the intense penultimate track – the genuinely horrifying “Kiss of Flesh”.

To say any more about the story itself would ruin it, but I’ll just reiterate one more time that the lyrics are fantastic. The music itself is very minimalistic, in some instances no more than an organ and a drum machine, however it’s always very fitting. It flows with the changes in tone of the story – I’d call the album a very well soundtracked audio book, if that didn’t sound like the least appealing thing in the entire world. Also, that downplays the quality of the music. The slow, subtle interjection of harsher and harsher rhythms over the course of the album as the story gets darker and more twisted is ingenious. But it’s the fact that the music is secondary to the lyrics here that I believe is my whole issue with getting people involved with this album – I shouldn’t be giving them God in Three Persons alongside instrumental post-rock or what have you. It needs to be treated on its own terms, in its own way.

But my intent is still in the right place. This is a fantastic album, and needs to be listened to.

In this vein:

The notes section on The Residents’ own website has some very interesting analysis of the themes in Gi3P.

Read part two of this article here.